The second week of October marked both Dyslexia Awareness Week and Dyspraxia Awareness Week 2020. Dyslexia and dyspraxia are important neurodiversity conditions. They are more widespread than many people realise, and deserve to be better understood. In this article, we talk about dyslexia and dyspraxia from our point of view as IP professionals. Each of us is working to promote inclusiveness in the workplace and the profession, and each of us has a personal perspective based on direct experience of neurodiversity.

What is neurodiversity?

In this article we focus on dyslexia and dyspraxia, but these are part of a wider group of conditions which also includes attention deficit (hyperactivity) disorder and autistic spectrum condition. Collectively, these come under the general umbrella of neurodiversity (they are also termed ‘specific learning difficulties’).

The term ‘neurodiversity’ recognises the fact that the human brain is configured differently in different people. Of course, this is true of all of us: some people are predominantly verbal, some are more visual, some are big-picture thinkers, some are more detail-oriented, and so on. We recognise this (or should do!) when we put together teams from members having complementary strengths.

In neurodivergent people, however, the differences are more pronounced. The precise neurological reasons for this are not known: neural connectivity may be a factor, as may differences in signalling between neurons or groups of neurons. Whatever the reasons, the consequence is that the neurodivergent brain processes information in significantly different ways compared to the neurotypical brain.

This may lead individuals to approach tasks in unusual ways. Neurodivergent people may have weaknesses in some areas of performance, but they often have particular strengths as well. They may also show surprising behaviours in the way they work or interact with others. In some cases, these cognitive and behavioural traits may be clear to see. In others, they may not: neurodivergence can be a so-called ‘hidden disability’.

As an IP professional, why should I be interested?

It’s estimated that as many as one in seven people are neurodivergent. Almost certainly, someone you know is affected by one of these conditions. It may be you, a member of your family, or one of your friends. It may be one of your colleagues: someone you manage, or who manages you, or a member of their family. It may be one of your clients or customers.

You may or may not be aware that that person is neurodivergent. Indeed, they may not realise it themselves if they are undiagnosed. But it will have an impact on how you and they interact, and lack of awareness can cause difficulties.

In the workplace, recognising and accepting difference is at the heart of ‘diversity and inclusion’ policies. Awareness is growing of the importance of valuing all of our colleagues, regardless of their gender, age, ethnicity, and so on. A good employer fosters a culture in which all colleagues feel able to bring their whole selves to work, confident that they will valued for who they are and supported to be the best they can be.

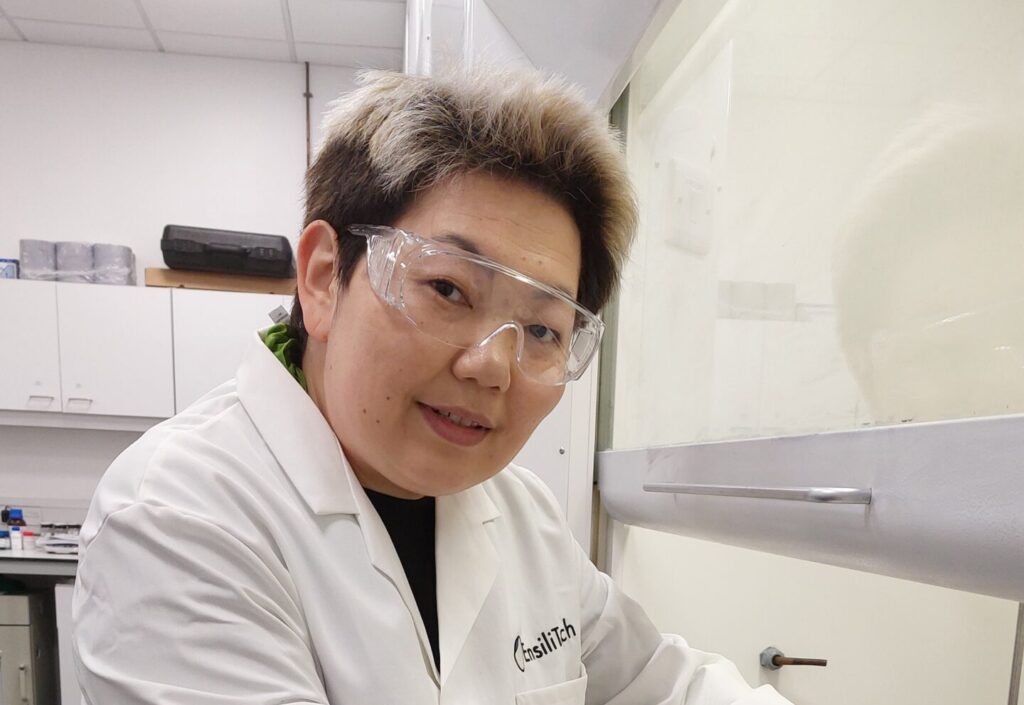

Readers of this article are likely to be IP professionals. Our clients and customers, the people who generate the inventions and works that are the stuff of IP, typically work in STEM or in the creative arts. It may be that, for many of them, their originality and innovation arises from being neurodivergent – in which case we owe our livelihoods, in part, to their neurodiversity!

As IP professionals, of course, we operate within a legal framework, and have typically undertaken legal training as well as training in STEM or humanities subjects. Although reliable statistics are not easy to come by, it seems likely that neurodiversity conditions are unusually prevalent in our profession. Supporting colleagues with dyslexia or dyspraxia to perform to their full potential benefits these individuals and our organisations alike.

What are the impacts of dyslexia and dyspraxia?

There is no simple or single answer to this question. One can list traits characteristic of dyslexia (problems with reading and writing) and dyspraxia (problems with movement and coordination). But not every dyslexic person will have all of the traits of dyslexia, and many of the traits are common also to dyspraxia.

It’s common for more than one neurodiversity condition to co-exist in one individual – or, looked at another way, there may be more overlap between, say, dyslexia and dyspraxia that the separate labels suggest. Neurodiversity is complex, and it’s crucial to avoid making generalisations. To say, for example, ‘a dyslexic person is like this…’ can be very misleading: every dyslexic person’s experience of their dyslexia is unique to them.

What is often true is that having dyslexia or dyspraxia causes a person to struggle at school, at university, or in the workplace. In consequence, they may not perform to their full potential, or a particular task may cost them more time, effort and stress than it would a neurotypical colleague. At least in part, this is because formal education methods and workplace practices tend to be geared around neurotypical people and can be inflexible.

If dyslexia or dyspraxia does cause a person to under-perform, colleagues or educators may draw mistaken conclusions about their intelligence. It’s therefore important to emphasise the fact that the neurodivergent population spans the same distribution of intelligence as the neurotypical population. However, a person with dyslexia or dyspraxia will often struggle, relative to their overall level of intelligence, with one or two particular cognitive skills. Indeed, it’s exactly these discrepancies that form the basis of diagnosis.

With the right support, however, the dyslexic or dyspraxic person can develop strategies and work-arounds that enable them to cope with their difficulties and unlock their full potential. Many neurodivergent people thrive in the workplace and perform at a high level, with little or no need for support. Indeed, it’s often the case that a weakness in one cognitive skill is counterbalanced by particular strengths in others. Thus lexical weaknesses may co-exist with excellent verbal or graphical ability, with creative, strategic and lateral thinking ability, with high emotional intelligence, and so on.

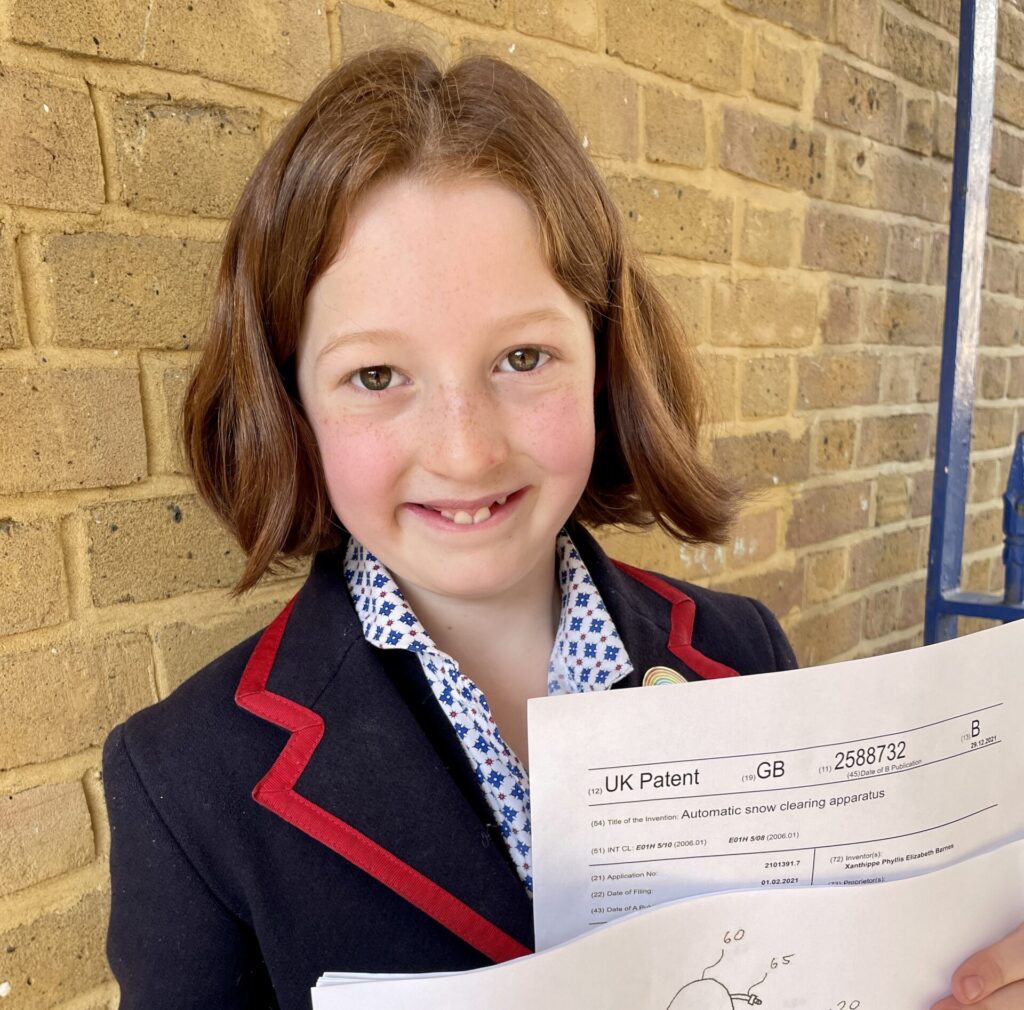

Sir Richard Branson, the Nobel prize winner Carol Greider and Sir Jackie Stewart are just three examples among many of people who have achieved remarkable success despite – or perhaps because of – being dyslexic. The self-awareness needed to implement the workarounds and coping strategies that neurodiverse people rely on often makes them especially aware of what their strengths are and how to play to them. Rather than think of dyslexia and dyspraxia as ‘problems’ to be ‘managed’, therefore, we should approach them simply as characteristics to be embraced, and offer support if it’s needed to help the individual to perform at their best.

Neurodiversity is sometimes wrongly assumed to be a form of mental health issue. It’s true that a neurodiversity condition, if it leads to significant difficulties, may lead to mental health issues for the person with the condition or for those close to them. In the main, however, one should not assume any link. A person with dyslexia, for example, may enjoy excellent mental health – and if they do suffer an episode of poor mental health, it is as likely as not to be for the same reasons as all of us, and wholly unconnected with their dyslexia.

Employers are sometimes nervous that employing and supporting neurodivergent employees will place an excessive burden on the business. This is unlikely to be the case. For one thing, what the Equality Act 2010 requires is ‘reasonable adjustment’. More to the point, the support needed often places little or no real burden on the employer. For example, it may simply amount to respecting a preference for verbal over written feedback, or understanding that using noise-cancelling headphones helps to cut down distracting background noise. Such adjustments amount to an investment in enabling the individual to work at their full potential, benefiting everyone.

What should I do?

The most important thing in the workplace, we believe, is to create a culture in which all staff are respected and valued. For colleagues with dyslexia or dyspraxia, this means building awareness and understanding of neurodiversity into our organisations, recognising the strengths that neurodivergent individuals bring, and being willing to provide support where needed. Most importantly, it means building trust, because it is only in an environment of trust that a neurodivergent colleague can feel comfortable disclosing their condition and discussing any support that they may benefit from.

In practical terms, it’s important to recognise that each person’s experience is individual to them. Dyslexia, for example, is a ‘spectrum condition’, meaning that two people with dyslexia may have quite different needs: one size does not fit all. The best approach is to ask the person, ‘how can I/the organisation best support you?’ Bear in mind that they may not be sure themselves, especially if newly diagnosed. Some experimentation and review may be needed to get things right.

Final thoughts

Dyslexia and dyspraxia (and neurodiversity conditions more widely) are a fascinating subject. Awareness is growing, but there is still much to do. All of us, as individuals and as organisations, should be thinking about these conditions, and building this thinking into our wider work on promoting diversity and inclusion.

Dyslexia and dyspraxia are sometimes seen as problems to be managed (or not…). Far healthier to value individuals with these conditions as people, and to celebrate the often remarkable contributions that they can make – with a bit of support, or perhaps some reasonable adjustment, where needed. It’s to everyone’s benefit to approach things that way, and it’s quite simply the right thing to do.

As IP professionals, we understand that IP protection exists to promote innovation. The prevalence of neurodiversity provides us with opportunities to innovate as colleagues and employers. Putting in place the right policies to support colleagues with dyslexia or dyspraxia helps them to be the best that they can be. In turn, this helps us to be the best colleagues that we can be.

Caelia Bryn-Jacobsen is a Partner at Kilburn & Strode, Stephen Driver is a Patent Examiner at the UK IPO, and Carolyn Pepper is a Partner at Reed Smith LLP.